Come Read With Us!

|

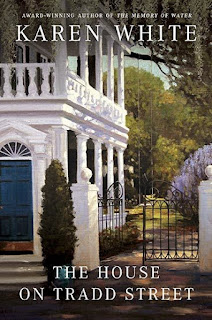

| With permission from Karen White. |

Excerpt.

Chapter 1

Pewter reflections of scarlet hibiscus colored the dirt-smudged windows of the old house, like happy memories of youth trapped inside the shell of an old man. The broken pediments over the windows gave the house a permanent frown, yet the leaf-filtered sun against the chipped Tower-of-the-Winds columns lining the side piazzas painted the house with hope. It was almost, I thought, as if the house were merely waiting for a miracle.

I studied the house, my Realtor’s mind trying to see past the wreckage. It was a characteristic Charleston single house, turned perpendicular to the street so that its short side abutted the sidewalk. The entry door, with an ornate cornice and Italianate filigree brackets, opened onto the garden-facing piazza, where I knew I would find the main entryway into the house. I wrinkled my nose, already smelling the inevitable decay I would encounter once I’d entered the house.

Despite the enviable south of Broad location, any potential buyer for this property would have to be blind or incredibly stupid. In my vast experience at selling historic real estate in the city, I would bank on the latter. The rhythmic pulse of rope against tree trunk punctuated the muggy Charleston morning air, catching my attention and drawing me to the peeling wrought iron fence to peer into the side garden. I wasn’t sure if it was curiosity that made me stop or just reluctance to continue. I hated old houses. Which was odd, really, since they were my specialty in the realty business. Then again, maybe not so odd, considering the origins of my dislike. Regardless, old houses gave me plenty of reasons to dislike them. For one thing, they smelled of lemon oil and beeswax mixed with mothballs. And always seemed to accompany the slow gait of an elderly person too old to keep up the house yet too stubborn to let it go.

Like the owner had exhausted all hope of finding something in the future that would ever be as good as the past. Depressing, really. It was all just lumber and plaster in the end. Seeing nothing, I pushed open the stubborn gate covered with climbing Confederate jasmine, the rusted hinges reluctantly giving up ground. I picked my way carefully over the cracked walkway of what must have once been a prized patterned garden, my high-heeled pumps avoiding cracks and tall weeds with prickers that would tear at my stockings and silk suit with little provocation. A fall of shadow from the rear of the garden caught my attention. Ignoring the drops of perspiration running down the front of my blouse, I gingerly stepped across the weeds to get a better look. An overgrown flower bed encircled a fountain where a cherub in the middle sat suspended in the perpetual motion of blowing nonexistent water from stone lips. Thick weeds as tall as my hips crept into the fountain, grasping at the cherub’s ankles. A gecko darted out from the chipped cement edging the fountain and ran along the side. Clutching my leather portfolio, I followed it to the back side of the statue, not completely sure why. Sweat trickled down my nape, and I raised a hand to wipe it away. My fingers felt icy against my skin, a sort of warning sign I had begun to recognize when I was still very small. I concentrated on ignoring the pinpricks that raced up my spine and made me listen to things I didn’t want to hear and that other people couldn’t. I was eager to leave, but I stopped at the sight of a splash of red while my beautiful and expensive Italian leather heels sank into thick mulch. A small kidney-shaped area had been cleared of weeds and there, sprouting from fresh cedar clippings, grew four fat bushes containing the most vibrant red roses I had ever seen.

They were like brightly dressed young girls sitting in the back pew of a crumbling church, and even their scent seemed out of place in the forlorn garden. I turned away, feeling an abiding sorrow that seemed to saturate the air in this part of the yard. The heat that pressed down on me seemed to have a cold center to it, and I felt out of breath, as if I’d run a long distance. Jerkily, I stumbled to the shade under a live oak tree. I leaned against the tree trunk and looked up, searching for my breath in a garden that seemed to be soaking up air and even time itself. Spanish moss draped shawllike on the ancient limbs of the tree, its massive branches testifying to its years on this earth, its roots reaching out toward the house.

The sound of the swing continued to reverberate throughout the overgrown garden, and when I turned my head, I again caught a movement of shadow from the corner of my eye. For a moment, I thought I could see a woman wearing an old-fashioned dress pushing an empty board swing suspended by rope from the oak tree. The image was hazy, the edges of it dim and fading. The pinpricks invaded the back of my neck again, and I abruptly turned toward the piazza and marched across the garden, unconcerned now about my panty hose or anything else except getting my errand over with. I crossed the marble-paved piazza, then pressed hard on the front doorbell and then again as I willed somebody to answer it quickly. It took forever before the slow, shuffling steps could be heard behind the closed door.

I saw movement through the beveled-glass window in the door, etched in the pattern of climbing roses, the pattern deflecting light and color and separating the person on the other side of the door into a thousand fragments. I sighed, knowing that it would take another five minutes for the old man to unlock all the dead bolts and another twenty for him to allow me to get to the point of our meeting just as surely as I knew that if I turned around to face the sound of the swing, I would see nothing at all. The door swung open, and I took a surprised step backward as I found myself staring up into large brown eyes magnified by what looked like the bottoms of Coke bottles stuffed into wire eyeglass frames. The man had to be at least six foot three, even with the hunched shoulders beneath the starched white oxford cloth shirt and dark jacket, and he wore a linen handkerchief neatly tucked into the coat pocket. I whipped out one of my business cards and held it out toward the old man.

“Mr. Vanderhorst? I’m Melanie Middleton with Henderson House Realty. We spoke on the phone yesterday.” The man hadn’t made a move to take my card and was still staring at me through his thick glasses. “We made an appointment for today so that we might discuss your house.”

He acted as if he hadn’t heard me. “I saw you in the garden.” He continued to stare and I rubbed my hands up and down my arms, feeling as if it were thirty degrees outside instead of ninety-eight. “I hope you don’t mind. I wanted to get a good look at the lot.” I turned to face the garden as if to illustrate my point and realized that the sound of the swing had stopped the moment the door opened. The lot itself was large by historic district standards, and I couldn’t help but think of the wasted space the house was occupying and how much more useful it would be as a parking lot for the nearby shops and restaurants. “Did you see her?” His voice startled me.

It was deep and very soft, as if it didn’t get much use, and he was unaware of how much breath he needed for each word. “See who?” “The lady pushing the swing.” He had my full attention now. I looked into his magnified eyes. “No. There was nobody there. Were you expecting somebody?” Instead of answering, he stepped back, opening the door farther, and made a courtly sweep of his hand. “Won’t you come in? Let’s sit in the drawing room and I’ll get us coffee.” “Thank you, but that’s really not necessa . . .” But he had already turned away from me and was shuffling through a keystone arch that separated the front hall from the stair hall. A faded yellow Chinese paper covered the walls, and I had the fleeting impression of elegant beauty before I looked closer and saw the buckling and the peeling and did a mental calculation of the cost of restoring handpainted wallpaper. I stepped through a pedimented doorway into the room Mr. Vanderhorst had indicated and found myself standing in a large front drawing room with tall ornamented ceilings capped with elaborate cornices circling the room.

A dusty crystal chandelier dominated the room, its remaining crystals seemingly held in place by thick cobwebs. An intricate plaster medallion on the ceiling above the chandelier finalized my initial impression of the room as a wedding cake that had been left out in a warm room too long. Smelling the old beeswax, I wrinkled my nose again, comparing my surroundings to my brand-new rented condo in nearby Mt. Pleasant complete with plain white walls, wall-to-wall carpeting, and central air. I would never understand people who felt privileged to pay a great deal of money to saddle themselves with a pile of termite-infested lumber like this, and then continued running themselves into bankruptcy from supporting the horrendous upkeep such an old house demanded. I shuddered, thankful that my own military-brat upbringing had never fostered any root-growing tendencies or warm and fuzzies toward ancient architecture. I looked around the room, careful not to touch anything that would get dust on my hands and clothes. Sheets covered most of what looked like antique furniture except for a faded grospoint-covered Louis XV armchair and matching ottoman as well as an enormous mahogany grandfather clock.

A small black-and-white dog lay curled on the ottoman and looked up with large brown eyes that strongly resembled those of my host. The thought made me smile until I spotted the huge crack in the plaster wall that snaked up from the baseboard to the cracked cornice in the corner of the room. My eyes drifted from the large water spot on the paint-chipped ceiling to the buckled wood floor underneath. I felt exhausted all of a sudden, as if I had somehow absorbed the age and decay of the room. I moved to one of the floor-to-ceiling windows, hoping daylight might perk me up. Pushing aside a faded crimson damask drapery panel, and almost choking on the smell of stale dust, I paused, wondering if the small etchings I saw on the wall were actually hairline cracks in the plaster. I leaned forward and squinted, wishing I’d brought my glasses.

A pale gray line stretched from the top of the baseboard to about four feet from the floor. Small markings bisected the line at approximately one-inch intervals, and tiny numbers were written in a delicate handwriting next to each demarcation. Squatting to see better, I realized I was looking at a growth chart, with the initials MBG written alongside the vertical line along with the age of MBG starting at one year. Tracing my finger along the line, I saw that it stopped at MBG’s eighth year. “That was mine.” The voice came from directly behind me, and I jumped, wondering how he had managed to move so quietly.

“But the initials . . . aren’t you Mr. Vanderhorst?” His eyes focused on the pencil marks on the wall, and I noticed that an antique writing desk had been pulled away from the wall to expose the marks and now stood almost in the middle of the room. “MBG stands for ‘my best guy.’ My mother used to call me that.” The soft tone of his voice reminded me of my own little-girl voice pretending to speak long distance on the phone to my absent mother. I looked away. A tray with delicate china teacups and a plate of pecan pralines had been laid on an uncovered side table. Moving toward it I spotted a large frame set on the table holding a sepia-toned portrait of a young boy sitting on a piano bench. Again, Mr. Vanderhorst’s voice sounded right in my ear. “That was me when I was about four years old. My mother was an amateur photographer. She loved to take my picture.”

He shuffled behind me and pulled off a dusty sheet from a delicate Sheridan armchair and indicated for me to sit. I sat, placing my leather portfolio on the floor by my feet, then leaned forward to spoon four cubes of sugar and a splash of cream into my coffee, noticing the rose pattern on the teacups. I had expected the ubiquitous antique blue-and-white Canton china found in most of the houses in Charleston’s historic district. The roses on this set of china were bright red with large blooms of layered petals, nearly identical to the roses I’d seen in the neglected garden.

I took a praline and placed it on a small rose-covered plate, then took another, aware of Mr. Vanderhorst watching me. Nervously, I sipped my coffee. “Those are Louisa roses—my mama’s hybrid and named after her. She cultivated those, you see, in the garden. They were famous for a while—famous enough to have magazines coming from all over to photograph them.” His eyes fixed on me behind the thick glasses, studying me as if to gauge my reaction. “But now the only place in the world you can find them is right here in my garden.” I nodded, eager to move on to the subject at hand. “Are you a gardener, Miss Middleton?” “Um, no, actually. I mean, I know what a rose is, and what a daisy looks like, but that pretty much covers all of my gardening terms.” I smiled tentatively. Mr. Vanderhorst sat down across from me in a matching chair and picked up a teacup with slightly trembling hands. “This house had beautiful gardens when my mother lived here.

Sadly, I haven’t been able to keep them up. I can just find enough energy to keep up the small rose garden by the fountain. That was my mama’s favorite.” I nodded, remembering the odd little garden and the sound of a swing, then took another sip of coffee. “Mr. Vanderhorst, as I mentioned on the phone yesterday, I’m a Realtor, and my real estate company is very interested in obtaining the listing for your house.” I set my cup down and reached inside my portfolio to pull out the information on the property values in the neighborhood, as well as brochures that explained why my company was better than any of the other dozens of real estate companies in the area. “You’re Augustus Middleton’s granddaughter, aren’t you? Your granddaddy and my daddy were at Harvard Law together, you know.

They even started out clerking in the same law firm, and Augustus was best man at my daddy’s wedding.” My arm felt awkward and heavy as I kept it extended in Mr. Vanderhorst’s direction while he ignored it. Finally, I leaned across and placed the information on the table between us, then picked up my coffee again. “Ah, no. I wasn’t aware that our families knew one another. Small world.” I took a quick sip of my coffee. “So, anyway, as I mentioned, my company is very interested—” “They had some kind of a falling-out when I was about eight. Never spoke to each other again. Saw each other occasionally across a courtroom but never exchanged another word.” I focused on swallowing without choking and breathing slowly, and made a conscious effort to still my leg from twitching.

Damn. Had Mr. Vanderhorst brought me out here just so he could tell me about my grandfather Gus? Was he about to ask me to leave? And couldn’t he have just told me this on the phone to save me the trouble? “Despite their disagreement, my daddy always thought him to be one of the most honorable men he’d ever met.” “Yes, well, he died when my father was only twelve, so I can’t really say.” “You favor him a great deal, you know. Your father, too, although we’ve never met. I’ve seen pictures of him and your mother in the paper every once in a while. You don’t look a thing like her.”

Thank God. If he started talking about my mother, I’d have to leave. There was only so much sucking up I was prepared to do to get this listing. “Look, Mr. Vanderhorst, I’ve got another appointment I need to get to, so I’d like to go ahead and discuss—” Once again he interrupted me as if I hadn’t spoken. He glanced down at the two pralines on my plate and seemed to grin. “Your grandfather had a legendary sweet tooth, too.” I opened my mouth to deny it, but Mr. Vanderhorst said, “Do you like old houses, Miss Middleton?” For a moment, I wondered if there were hidden cameras pointed on me to be replayed later on one of those stupid reality television shows.

I felt my mouth working up and down as I tried to figure out how truthful I should be. As if not wanting to hear outright lying, the little dog jumped off the ottoman, gave me a withering look, then ran out of the room. “They’re, um, well, they’re old. Which is nice.” Brilliant. “What I meant to say is that old houses are really popular right now in today’s real estate market. As you probably already know, prices and interest in historic real estate have increased dramatically since the nineteen seventies when the Historic Charleston Foundation sponsored the restoration of the Ansonborough neighborhood. People are buying old houses as investment properties, fixing them up, then selling them for a nice profit.” I risked taking another sip of coffee, hoping he wouldn’t steer the conversation away again. I eyed the pralines, still untouched on my plate, and decided that eating one would give Mr. Vanderhorst too much of a chance to change the conversation again. “As I said on the phone, your lawyer, Mr. Drayton, contacted us about possibly listing your house. I understand that you’re thinking about moving into an assisted-living facility and have no relatives who would be interested in owning the home.” While I spoke, Mr. Vanderhorst left his untouched coffee and pralines and walked to one of the tall windows that looked out into the garden. I could see part of the old oak tree from where I sat. I paused, waiting for him to confirm what I had just told him and took the opportunity to bite into a dark chocolate praline.

His voice was soft when he finally spoke. “I was born in this house and I’ve lived here my entire life, Miss Middleton. As did my father, and grandfather, and his grandfather before him. This house has been lived in by a member of the Vanderhorst family since it was built in 1848.” The chocolate stuck in my throat. Here it comes. He’s not selling the house and I’ve just wasted an entire morning. I swallowed and waited for him to continue, my conscience tugging at me, reminding me of almost identical words my mother had once said to me. But that had been a long, long, time ago, and I was no longer that girl who had listened with so much hope in her heart.

“But now I’m the only one left. All of those generations before me who worked so hard to keep this house in the family. Even after the Civil War, when things were tight, they sold their silver and jewelry and went hungry just so they could hold on to this house.” He turned to face me, as if remembering that I was in the room. “This house is more than brick, mortar, and lumber. It’s a connection to the past and those who have gone before us. It’s memories and belonging. It’s a home that on the inside has seen the birth of children and the death of the old folks and the changing of the world from the outside. It’s a piece of history you can hold in your hands.” I wanted to add, It’s an unbearable weight of debt hanging around your neck, pulling you down until you land face-first into insolvency. But I didn’t say anything because Mr. Vanderhorst’s face had lost its color, and he seemed to be swaying on his feet. I jumped up and led him to his chair, then handed him his cup of coffee.

“Can I call a doctor for you? You’re not looking well.” I put the coffee on the table next to him and took his hand, remembering what he’d said about his house. It might be just brick and mortar to me, but it was his whole life—a life nearing its end with no family left to refurbish the garden or enjoy the rose china. It saddened me and I didn’t want it to, but I held tight to his hand anyway. He ignored the coffee. “Did you see her? In the garden—did you see her? She only appears to people she approves of, you know.” I was torn between answering him and calling his doctor. But something he had said I had heard before and once, a million years ago, I had believed with all my young and gullible heart. It’s a piece of history you can hold in your hands. I looked into his eyes and allowed myself to see his need and understand his pain.

Taking a deep breath, I said, “Yes. I saw her. But I don’t think it’s because she approves of me. I . . . seem to see things that aren’t there on a kind of regular basis.” Some of the color returned to his face, and he actually smiled. He leaned over and patted me on the leg. “That’s good,” he said. “That’s very good news.” He leaned back and drank his coffee in three big gulps before standing as if nothing had happened. “I hope you don’t mind me ending our nice meeting so abruptly, but I have a few things I need to do this morning before my lawyer arrives.” He pulled a clean linen napkin off the serving tray and put the pralines, complete with the rose-covered china plate, into it before twisting the napkin into a knot on top and handing it to me. I stood, stunned, his actions again rendering me speechless. Finding my voice, I blurted out, “But we haven’t even discussed . . .” I took the napkin-covered plate as he shoved it into my hands. “And I can’t take your plate. I don’t know when I’ll be back this way to return it.” He waved his hand in dismissal. “Oh, never you mind about that. It will be back amongst the other plates sooner than you’d think.”

I wanted to be angry over wasting my morning for a pointless visit. But when I looked down at the plate in my hands, all I could feel was a peculiar regret. Over what? It’s a piece of history you can hold in your hands. Once again, I was seven years old and standing hand in hand with my mother in front of another old house. I felt in my bones what Mr. Vanderhorst was talking about, no matter how much or how long I wanted to deny it, and I allowed a foolish tenderness toward the old man to shake my heart loose.

Mr. Vanderhorst leaned across and gently kissed my cheek. “Thank you, Miss Middleton. You’ve done this old man a world of good by your visit today.” “No, thank you,” I said, surprisingly close to tears. It had been a long time since anyone had kissed me on the cheek, and for a moment I wanted to ask if I could stay for a while longer, eating pralines and drinking coffee while chatting about old ghosts—both the living and the dead kind. But Mr. Vanderhorst had already stood, and the moment passed. Mechanically, I hung my portfolio over my shoulder and clutched the loaded napkin carefully as Mr. Vanderhorst led me to the front door.

We passed a music room dominated by a concert grand piano, and I remembered the photo of the little boy sitting on the bench. I didn’t have time to linger as Mr. Vanderhorst’s surprisingly strong hand on my back propelled me toward the front door. For a man who shuffled, he seemed determined to get me out of the house. Which was fine with me, really. I’d wasted enough of my day. I stepped outside onto the piazza and turned back to say goodbye. He was beaming now, his eyes bright, shiny pennies behind the thick glasses. “Goodbye, Mr. Vanderhorst. It’s been a pleasure meeting you.” I was surprised to find that I really meant it. “No, Miss Middleton. The pleasure was all mine.” I walked down the piazza toward the door leading to the sidewalk, feeling his gaze on me. When I got to the door, I remembered the plate I was holding. I turned and saw Mr. Vanderhorst watching me from the doorway of the house, as much a part of it as the piazza columns and leaded-glass windows. “I’ll bring back the plate as soon as I can.” I even imagined I’d look forward to a return visit. “I have no doubt that you will, Miss Middleton. Goodbye.” I opened the door, then shut it behind me, feeling him watching me through the garden gate until I disappeared from his view. I didn’t once turn toward the garden, where the sound of a rope swing against old bark had once again begun to punctuate the muggy morning air.

Comments

Post a Comment